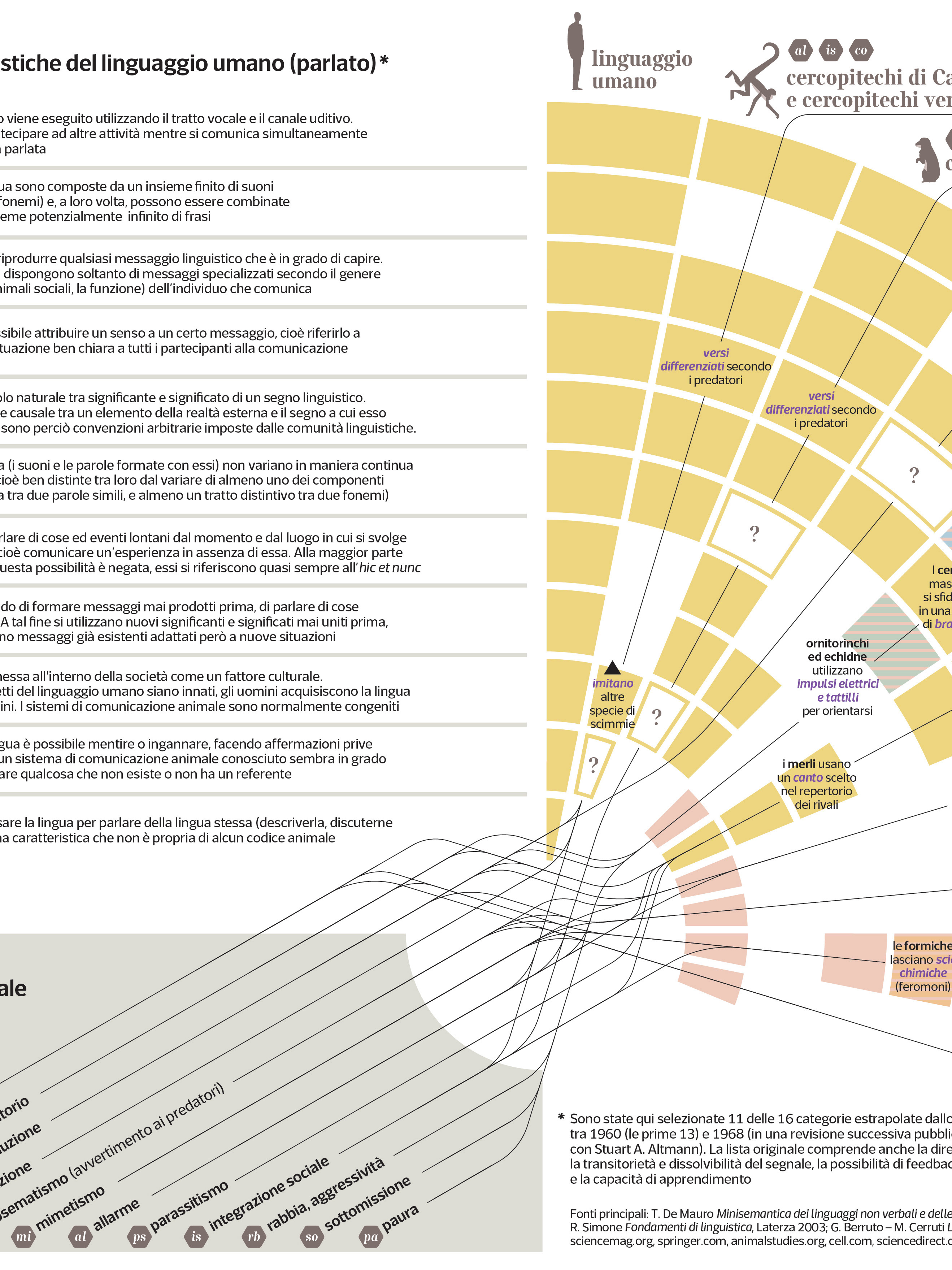

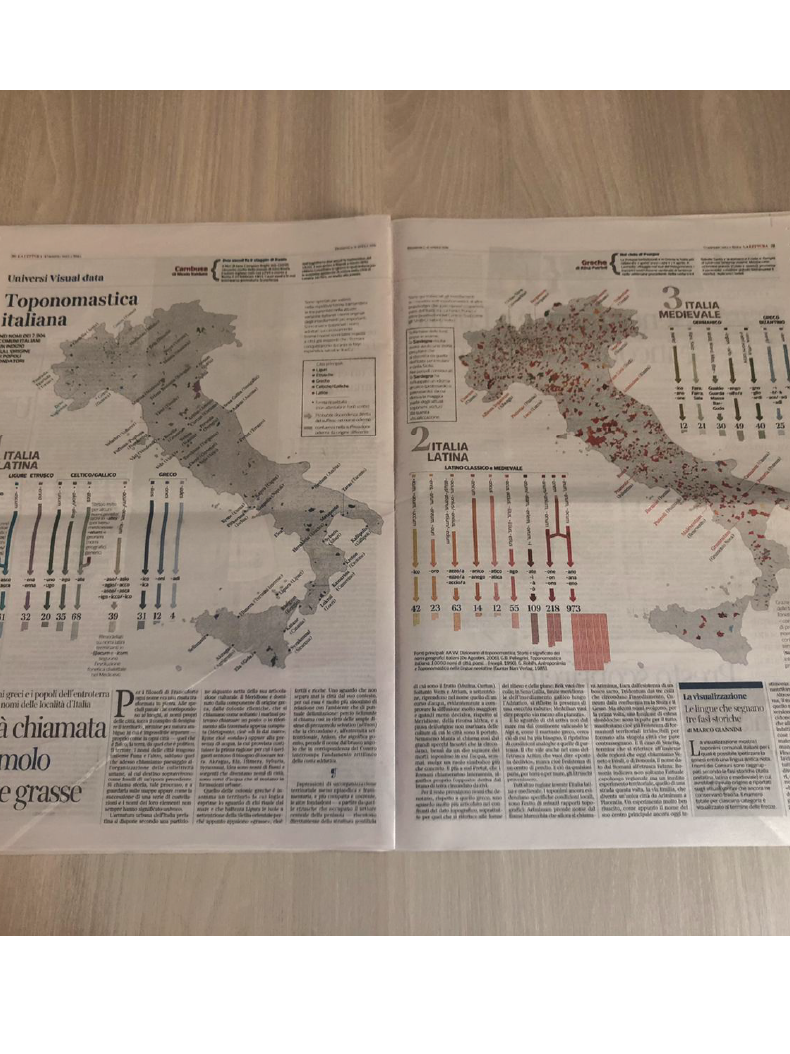

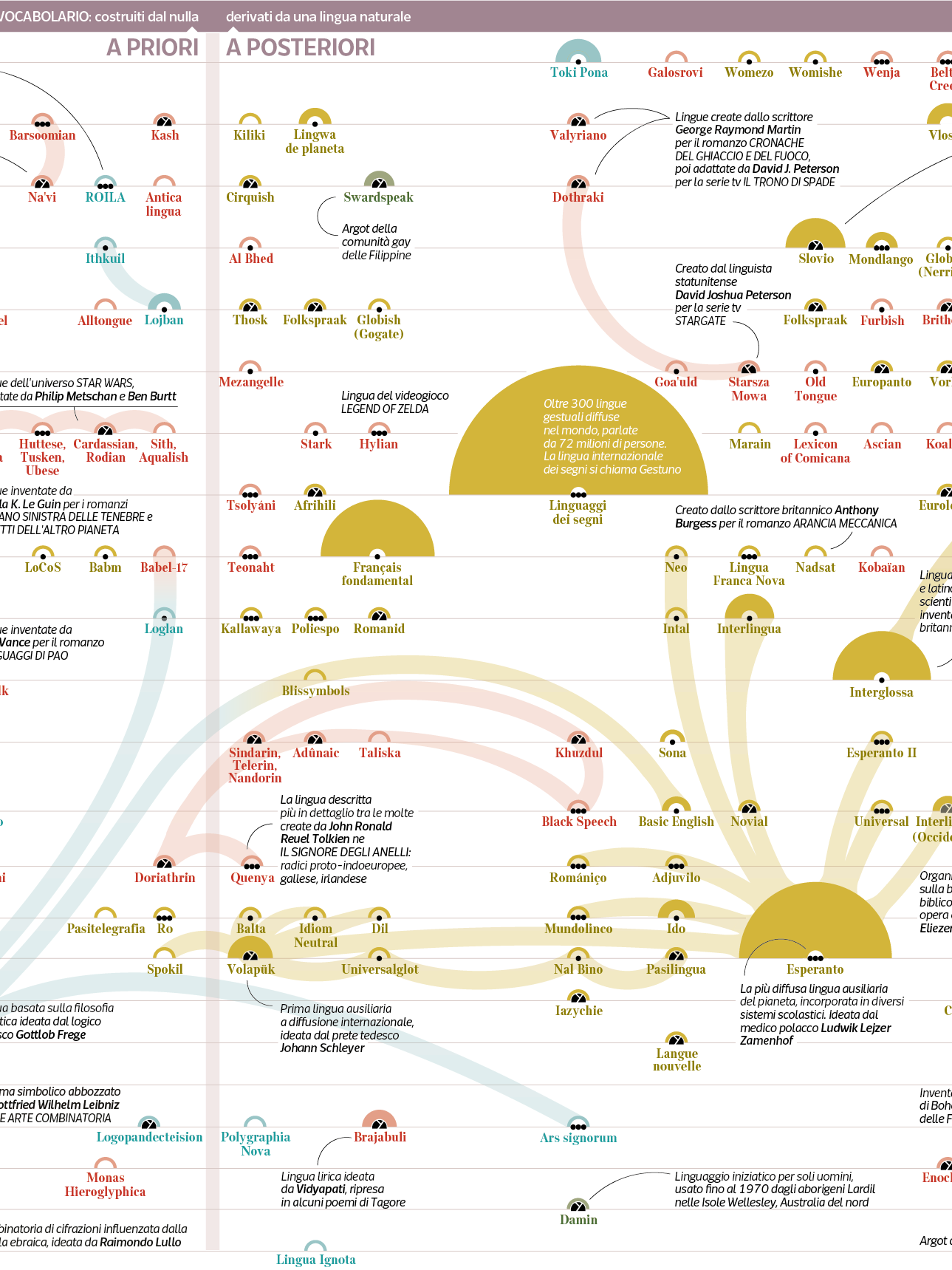

A new visualization for @la_lettura 553 (2nd July 2022) on the etymology and history of the names of European nations.

It shows the name of many European countries in their national language and the name used to call them in 15 European languages.

As many of those names given in other languages have a common origin, they also share the same etymology, which is clustered together to evidentiate the linguistic group and family it comes from. Each primitive name is then reported in the note section on the bottom.

These primitive names, then handed down to other languages, refer to the most ancient attestation note or presumed date of appearance of the term. The attestation is connected on a timeline that crosses the infographics along the diagonal.

The nations and their names appear in black when they are endonyms and yellow when exonyms.

These two terms, coined in contrast to each other, are what geography and cartography hold as the "official name" of a locality (or in general, of a geographical entity). But they are also used in Linguistics.

As many of those names given in other languages have a common origin, they also share the same etymology, which is clustered together to evidentiate the linguistic group and family it comes from. Each primitive name is then reported in the note section on the bottom.

These primitive names, then handed down to other languages, refer to the most ancient attestation note or presumed date of appearance of the term. The attestation is connected on a timeline that crosses the infographics along the diagonal.

The nations and their names appear in black when they are endonyms and yellow when exonyms.

These two terms, coined in contrast to each other, are what geography and cartography hold as the "official name" of a locality (or in general, of a geographical entity). But they are also used in Linguistics.

Endonym is the name of a nation, or more generally of a geographical feature, in an official or well-established language occurring in that area where the feature is situated. Examples: Vārānasī (not Benares); Aachen (not Aix-la-Chapelle); Krung Thep (not Bangkok); Al-Uqşur (not Luxor).

Exonym is, in contrast, the name used in a specific language for a feature situated outside the area where that language is widely spoken, and differing in its form from the respective endonym(s) in the area where the feature is situated. Examples: Warsaw is the English exonym for Warszawa (Polish); Mailand is German for Milano; Londres is French for London; Kūlūniyā is Arabic for Köln. The officially romanized endonym Moskva for Mocквa is not an exonym, nor is the Pinyin form Beijing, while Peking is an exonym.

Exonym is, in contrast, the name used in a specific language for a feature situated outside the area where that language is widely spoken, and differing in its form from the respective endonym(s) in the area where the feature is situated. Examples: Warsaw is the English exonym for Warszawa (Polish); Mailand is German for Milano; Londres is French for London; Kūlūniyā is Arabic for Köln. The officially romanized endonym Moskva for Mocквa is not an exonym, nor is the Pinyin form Beijing, while Peking is an exonym.

Even with these definitions, however, there remain doubts about the precise nature of endonyms and exonyms, as they have a precise meaning for the many who use them, but create an issue about belonging.

A place, whatever it is, and the name it carries requires space in its definition. When a name is given and pertains to such attributes as the place itself is associated with, it accrues cultural, emotional, political, social, and spiritual involvements from the place itself.

The name becomes a symbol, to some extent. This is arguably the destiny of every word that lives long enough to be spoken and written many times, but it's remarkably true for the name of a nation. As long a nation has a history, a legacy, estimators, and even enemies, its different names entail these relationships.

The American historian and professor George R. Stewart classifies toponyms as descriptive, associative, incident-related, possessive, commemorative, commendatory, folk-etymological, manufactured, or originating in error. He added a psychological layer to the consideration of a place, that matters in studying its etymology:

'A place, therefore, is any area which an observing consciousness, whether human or animal, distinguishes and separates, by whatever means, from other areas. The boundaries may be precise or vague; they may be physical and concrete or mental and imaginary. A place may be a natural feature or a human construction. ... To be named, a place must first be conceived as an entity, that is, as being separable and identifiable from other places'.

'A place, therefore, is any area which an observing consciousness, whether human or animal, distinguishes and separates, by whatever means, from other areas. The boundaries may be precise or vague; they may be physical and concrete or mental and imaginary. A place may be a natural feature or a human construction. ... To be named, a place must first be conceived as an entity, that is, as being separable and identifiable from other places'.

All being said, it can be generally said that endonyms and exonyms are respectively bottom-up

and top-down approaches to toponyms and their implications. The former approach, with the people on the spot being its originators, is felt as collective property, a reflection of the individual's right to choose the name and the language/dialect.

In some cases, it can be the State that determines an endonym, as happened with some ideologically-driven monikers in the Soviet Union during the communist era. The State can determine which endonyms are official and standardized, through legislation on orthographic rules, for example. And this can be the case for exonyms as well.

Even those names out of the officially stated lists, however, remain names, albeit a limited value outside their own immediate locale: Hungarian language names in parts of Romania, such as Segesvár for the town known in Romanian as Sighişoara, have consistently remained endonyms because of the long-standing and well-established Hungarian community present there, notwithstanding the fact that official status for the Hungarian language in those parts of Romania has been absent for several decades. And such examples can be found worldwide.

We give a name to what we need to name. Whether in our possession or not